Pharmacologic Options for Treatment-Resistant Depression: An Expert Interview With Charles B. Nemeroff, MD, PhD

Depression: An Expert Interview With Charles B. Nemeroff, MD, PhD

Posted 06/09/2008

Charles B. Nemeroff, MD, PhD Author Information

Editor's Note

Treating depression is seldom as simple as prescribing an antidepressant. Some patients fail to improve enough to resume normal life activities, and many others continue to have bothersome symptoms that prevent full functioning. Charles B. Nemeroff, MD, PhD, is a leading researcher in the field of mood disorders. He is the Reunette W. Harris Professor and Chairman of the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences at the Emory University School of Medicine in Atlanta, Georgia. On behalf of Medscape, Randall F. White, MD, asked Dr. Nemeroff for an update on managing treatment-refractory depression.

Medscape: All psychiatrists and some primary care providers see patients with depression who just don't seem to get better with a course of antidepressant medication. At some point, a patient might be considered resistant to treatment .What is the prevailing definition of treatment-refractory depression (TRD)?

Charles B. Nemeroff, MD, PhD: There are a number of definitions, but in reality, they are not very established in practice. The accepted research definition from the work of Michael Thase and colleagues[1] is a failure of trials with 2 antidepressants that have distinct mechanisms of action. But that is probably an oversimplification of the problem because it depends on how you define response. If you define response as a 50% improvement in depressive symptoms, then response rates are relatively high; but if a patient begins treatment with a Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS) score of 35 and ends up, after 12 weeks, with a HDRS score of 17, that change may qualify as treatment "response" even though the patient remains quite symptomatic. I, however, would not consider that patient to be optimally treated.

Recently we have come to use remission as an endpoint, which is arbitrarily defined as scoring under 7 or 8 on the HDRS, and some researchers are even talking about recovery, defined as having a HDRS score of less than 4. So if you start looking at it that way, which means a return to the premorbid, virtually asymptomatic state, TRD is indeed a large population.

Medscape: How common is the problem of TRD in psychiatric practice and in the general population?

Dr. Nemeroff: Extremely common. In the Sequenced Treatment Alternatives to Relieve Depression (STAR*D) study, only 28% of patients treated with open label citalopram exhibited remission.[2] That means that 72% didn't, which is pretty remarkable given 14 weeks of treatment with a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI).

Medscape: In a review article you wrote, you mentioned a TRD prevalence in the general population of 2%-3%.[3]

Dr. Nemeroff: That article used the strictest definition of treatment resistance, which doesn't include partial responders. I think the data are simple in terms of monotherapy: at best, a third of patients achieve remission. If a failed trial with a single antidepressant were considered treatment resistance, it would encompass two-thirds of patients. In the second wave of STAR*D, another 25% of patients achieved remission, either with switching[4] or augmentation.[5] So in that study, with 2 antidepressant trials, 50% of patients entered remission.

Most people in practice would say that 30% of the patients that they treat have TRD.I would say, using more stringent criteria, it is closer to 40% or 50%.

Medscape: How much disability is associated with TRD?

Dr. Nemeroff: A huge amount, with a high rate of unemployment or missed work days; and impairment on measures of quality of life and functional outcomes, such as impaired ability to experience pleasure, and impaired family interactions. It takes a terrible psychosocial toll, and also a large medical toll because depressed patients are at increased risk for a variety of other medical disorders, such as heart disease and stroke. The literature on heart disease and depression is vast. [6]

Medscape: How much does medical or psychiatric comorbidity contribute to TRD?

Dr. Nemeroff: A number of occult medical disorders, if left untreated, are associated with TRD. The leading cause is occult hypothyroidism. Patients with primary hypothyroidism do not respond to antidepressants at all, which has been well-researched.[7]

Medscape: What about psychiatric comorbidities and treatment resistance?

Dr. Nemeroff: Anxiety disorders are highly comorbid with depression and inevitably impede treatment response. Patients with panic disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, and social anxiety disorder are more likely to exhibit treatment resistance compared with patients who have uncomplicated major depression.[2]

Medscape: Can you briefly outline the pharmacologic strategies for managing TRD?

Dr. Nemeroff: We have 2 main pharmacologic approaches: switching and augmentation. In switching, most practitioners choose a medication with a different mechanism of action from the first one. For example, if a patient had not responded to an SSRI, you might choose a serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI); an atypical antidepressant such as bupropion, mirtazapine, or nefazodone; or a monoamine oxidase (MAO) inhibitor or tricyclic antidepressant. Yet in the STAR*D trial, 25% of patients who did not respond to citalopram responded to sertraline.[4] Both are SSRIs, but they are different in some ways: sertraline has some affinity for the dopamine transporter whereas citalopram does not.

The augmentation strategy includes either augmentation with an agent that in and of itself is not an antidepressant but can enhance the effects of the antidepressant, or combining the initial antidepressant with a second antidepressant. This is not without some ambiguity because, for instance, quetiapine is a second-generation antipsychotic (SGA) that actually has antidepressant properties of its own. Be that as it may, the traditional strategies are thyroid hormone (T3), 25-50 micrograms daily, and lithium.

The data for T3 are discordant, with both positive studies and negative studies. It can get confusing because some investigators have tried to use T3 to accelerate antidepressant response in depressed patients receiving initial treatment, and thus to convert nonresponders to responders. A recent study did find an effect of T3, but it was not in TRD patients.[8] We have done a similar study, which has been presented but not yet published, and did not see any beneficial effect of T3.

Medscape: They also used T3 in STAR*D.[9]

Dr. Nemeroff: Yes, with a 23% response rate.

Medscape: It actually came out ahead of lithium.

Dr. Nemeroff: It did better than lithium, which had an 11% response rate, but the difference between lithium and T3 was not statistically significant because of the small numbers of patients.

The problem with this part of the STAR*D trial was that they used a lithium dose of 900 mg per day. Why would you limit lithium to such a low dose? We know that most patients require higher doses.

Lithium is a clear choice for antidepressant augmentation, but more studies have been conducted with tricyclics than with SSRIs or SNRIs. Although lithium may have a lot of side effects, it is the only medication that has been shown to reduce suicide, which is a major advantage.[10]

Medscape: The second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs) show promise in TRD. Which ones have been studied and what does the latest research tell us about their usefulness?

Dr. Nemeroff: My research team published a report in Neuropsychopharmacology,[11] Mahmoud and colleagues published a study late last year,[12] and our group together with the Brown University group conducted a third study that is now in press.[13] All 3 studies show that risperidone is effective in TRD to a greater or lesser extent.

Shelton and colleagues performed the original research on olanzapine in combination with fluoxetine. [14] Three augmentation studies with quetiapine have been presented but are not yet published.[15] No controlled trial data exist for ziprasidone or clozapine, although open-label studies are available. And of course, after our initial pilot observations, aripiprazole was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) as an adjunctive to an antidepressant for treatment of major depression.[16]

Medscape: Are you aware of distinctions among these SGAs in efficacy, safety, and tolerability for this indication? How does the clinician make the decision to use one?

Dr. Nemeroff: No one has conducted head-to-head comparisons among them. I think the decision comes down to side effects. Olanzapine and quetiapine have the burden of weight gain and potential for diabetes and metabolic syndrome. Risperidone has the burden of extrapyramidal side effects at higher doses and possibly tardive dyskinesia, as well as a tendency to increase prolactin secretion. So none of them is perfect.

Medscape: In your opinion, when would a clinician actually consider using one of these agents for TRD?

Dr. Nemeroff: I am not in any way opposed to using SGAs early in the course of TRD. If a patient is having trouble sleeping, a medication such as quetiapine could be very helpful. The patient can receive immediate benefit from improved sleep, and then during the next couple of weeks, depression should also improve.

When I am treating patients who have TRD, I sit down and tell them about the panoply of available treatments, including cognitive-behavior therapy (CBT), which can be done in conjunction with taking medicine. Depending on how depressed they are, I will talk to them about other nonpharmacologic options, such as electroconvulsive therapy, and perhaps repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation, which is awaiting approval by the FDA.[3]

I describe the various medication possibilities: combination therapy, such as venlafaxine plus mirtazapine; MAO inhibitors, clearly effective agents for the treatment of depression, and especially atypical depression; tricyclic antidepressants with all the side effects of each. I go over some of the newer, off-label options such as the anti-Parkinson drugs pramipexole and ropinirole, for which there are some data on efficacy. [3]

Medscape: You already referred to this briefly, but what is the role of psychosocial intervention for patients with TRD?

Dr. Nemeroff: I think its role is big, but the problem is that not many practitioners, particularly psychiatrists, are skilled in CBT. The evidence is that CBT added

Introduction to Female Sexual Dysfunction

Female sexual health is a dynamic and multifaceted phenomenon that is closely linked to a woman's overall quality of life. Sexual dysfunctions can interfere with intimacy, affect a martial relationship, and ultimately erode well-being and overall health. Determining the etiology of sexual complaints in women is often a complex process; the healthcare provider must be a cautious detective, exploring both the medical and psychological issues that can influence the sexual response cycle. An analysis of data on more than 1700 women aged 18-49 from the National Health and Social Life Survey suggested that the incidence of sexual complaints in women was approximately 43%, with diminished desire being the most frequent disorder cited.[1]

The physiology of the female sexual response involves more than the genital pelvic organs (vulva, clitoris, labia majora and minora) and the internal pelvic structures (vagina, uterus, ovaries, and fallopian tubes). The spinal and central nervous system are also major contributors as are a number of areas of the brain, including the hippocampus, hypothalamus, limbic system, and medial preoptic area. Also implicated in the response cycle are neuropeptides like serotonin, dopamine, norepinephrine, epinephrine, opioids, nitric oxide, acetylcholine, and vasoactive intestinal peptide. Sex steroids, estradiol and testosterone, are essential in the female genital response and normative functioning of the response cycle.

Etiology

There are many causes, both direct and indirect, of female sexual dysfunction. Acute or chronic bodily illness, psychological problems, and interpersonal conflicts can all have an impact on a woman's sexual response or motivation.

Biological Factors

Chronic illnesses that have been implicated in sexual dysfunction include:

- Cardiovascular diseases;

- Diabetes;

- Autoimmune syndromes; and

- Neurologic impairment.

Sexual anatomy, physiology, and normative response may also be affected by malignancy, urologic or gynecologic problems, and endocrinopathies. Estrogen depletion from natural, surgical, or chemically induced menopause, as well as premature ovarian failure,[2] may cause vaginal dryness and menopausal syndrome which can lead to sexual complaints. Young women who have either anorexia- or exercise-induced amenorrhea, bulimia, or who have had chemotherapy or radiation may also experience vaginal atrophy and sexual dysfunction.[2] Lactation-induced amenorrhea is common in women who are breastfeeding; postpartum women may also suffer from hypoestrogenemia, vaginal dryness, and atrophic complaints.

Psychological Factors

Interpersonal conflicts such as marital infidelity, as well as psychiatric illnesses such as depression, anxiety, or substance abuse, can also have an adverse effect on sexual function, as can past history of sexual abuse or physical violence. Additional factors that can contribute to sexual problems include:

- Marital discord;

- Poor partner health;

- Cultural conflicting mores;

- Lack of privacy;

- Poor relationship trust and quality;

- Poor technical skills in the partner; and

- Sexual naiveté about anatomy and orgasmic response.

Medications

In addition to acute or chronic health conditions, many medications have been implicated in detrimental sexual response. The common culprits include:

- Psychotropic medications, including antipsychotics, mood stabilizers, and serotonin reuptake inhibitors;

- Many cardiovascular agents;

- Histamine receptor blockers; and

- Oral contraceptives.

AFUD Classification

According to the revised definitions of the American Foundation of Urological Diseases (AFUD), there are 5 categories of female sexual complaints:

- Hypoactive sexual desire disorder -- persistent or recurring deficiency or absence of sexual fantasies, thoughts, or receptivity to sexual activity that causes personal distress.

- Sexual aversion disorder -- persistent or recurring phobic aversion and avoidance of sexual contact that causes personal distress and can be a result of physical or sexual abuse or trauma.

- Sexual arousal disorder -- has many subtypes, including subjective arousal disorder, genital arousal disorder, and combined arousal disorder. Arousal disorders are the persistent or recurring inability to attain or maintain sufficient sexual excitement, causing personal distress.

- Orgasmic disorder -- persistent or recurrent difficulty in delay in or absence of attaining orgasm after sufficient sexual stimulation and arousal, causing personal distress.

- Sexual pain syndromes -- include dyspareunia, vaginismus, and other pain disorders

| ||||||||||

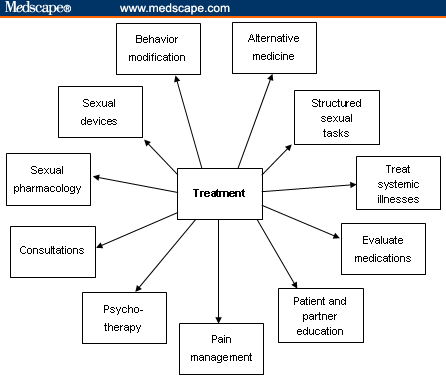

Treatment: Multidisciplinary ApproachThe management of female sexual dysfunction is a complex process that requires addressing underlying medical issues coupled with treatment of psychological or psychosexual barriers. Often, several healthcare providers are involved in the dynamic treatment process for a given individual; the primary provider should have access to many specialists within his or her community. See Figure 2.  Figure 2. Treatment algorithm. Adapted from Krychman ML. Female sexual dysfunction. Female Patient. 2007;32:47-48. Internal Medicine and PharmacologyChronic systemic illnesses, such as hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, and/or an underlying thyroid dysfunction, can be contributing factors in sexual dysfunction. Treatment of these conditions accordingly can alleviate sexual problems. Consultation with the patient's primary care provider can be very helpful. As described in the history section, careful identification of medications is also essential; antidepressants and antihypertensive medications can have effects on sexual desire, arousal, and orgasm. Occasionally, medication regimens can be modified by altering dosing and/or time intervals or specific drug classes to decrease sexual side effects. The referral to a psychopharmacologist may be necessary. Behavioral and Lifestyle ModificationsBehavioral and lifestyle modifications can improve overall quality of life and sexual function. A well-balanced diet, active exercise regime, discontinuation of tobacco use, and minimizing alcohol consumption should all be encouraged. Structured sexual tasks, such as the following, should also be encouraged:

Fatigue and poor sleep patterns may hinder sexual connectedness. The prescription should be for frequent naps or rest and instruction to plan sexual intimacy when well rested and fatigue is at a minimum. Education concerning alternate forms of sexual expression, such as mutual massage; intimate fondling and caressing; or manual, digital, or oral stimulation should also be introduced to the couple to allow for sexual exploration and enhanced sexual communication. Innovative sexual techniques or positions may help the couple reduce sexual boredom as well. Patients and their partners should be encouraged to experiment as they are comfortable with alternative sexual positions. Side-to-side or female superior position may help limit deep pelvic thrusting, which can minimize vaginal discomfort for atrophic women. It also allows for direct clitoral stimulation, which many women find pleasurable. A comprehensive sexual health program should also encourage techniques such as warm soaks to help decrease muscle tension and extensive physical therapy to help relax tense muscles. Guided imagery, quiet meditation, deep-muscle relaxation, and avoidance of lethargy are options that can be explored as well. Pain ManagementIn patients for whom pain is an element of sexual dysfunction, consultation with pain management specialists is essential. These specialists can help in adjusting opioid regimens, adding adjunctive analgesics, and modifying dosing schedules to decrease fatigue and lethargy while maintaining adequate pain relief. Patient EducationThe education of patients concerning normal genital anatomy and how the disease or therapeutic procedures have affected sexual anatomical functioning is important. The use of a handheld mirror during the pelvic examination can help the patient identify her own anatomical structures. Discussion concerning the Gräfenberg spot (G spot); clitoral, vaginal, and uterine orgasms; and dispelling some long-held sexual myths is also important. Take-home items such as pamphlets, books, videos, DVDs, and other visual aids can provide reinforcement and future reference for the patient and her partner. There are many important books on sexual exploration, and a comprehensive list of books both for erotic reading and self-education can be helpful. The American Cancer Society's booklet entitled Sexuality for Women and Their Partners[7] is an excellent patient reference guide for the patient who has sexual complaints as a result of her cancer diagnosis or treatment. Information concerning sexual devices and accessories can also be given to the patient. Sexual accessories such as self-stimulators can be encouraged as part of the sexual health treatment plan. Legitimate Web sites and Internet links should also be recommended to the patient as part of her comprehensive sexual education program. Sexual health organizations such as the International Society for the Study of Women's Sexual Health, the Women's Sexual Health Foundation, and the Alexander Foundation for Women's Health are only a few of many excellent resources. (See "Resources" at the end of this article.) Sexual TherapyCertified sexual therapists are trained to deal with patients who have:

Patients should be offered cognitive-behavioral therapy; brief intervention therapy; or marital, individual, couples, or group therapy by a trained therapist who deals with sexual issues. MenopauseThe following lifestyle changes can help manage troublesome hot flashes for menopausal women[8]:

Some nonestrogen medications (serotonin reuptake inhibitors, clonidine patch, megestrol acetate) can be used to help reduce hot flashes when systemic estrogen is contraindicated or declined by patients. LubricationNonmedicated, nonhormonal vaginal moisturizers and lubricants may be useful for women who experience vaginal dryness and painful intercourse, especially women who decline or are not candidates for minimally absorbed local vaginal hormones. Vitamin E gel capsules can be punctured with a pin and then inserted into the vagina.[9] Another method is to instruct the patient to empty the capsule's contents onto her finger and gently insert it circumferentially within the vagina. An over-the-counter polycarbophil-based vaginal moisturizing gel (Replens; Lil' Drug Store Products; Cedar Rapids, Iowa) can be used for the treatment of vaginal atrophy. When applied to the vaginal epithelium, it produces a moist film over the vaginal tissue which remains attached to the epithelial surface, providing lubrication. Replens has also been shown to restore vaginal pH measurements to premenopausal values.[10] The healthcare provider should also caution patients to read the labeled ingredients of the moisturizers. Women with severe vaginal atrophy should avoid additives in lubricants such as colors, flavors, spermicidal agents, bactericides, or warming ingredients, as these may irritate the vaginal lining.[11] Vaginal lubricants are typically used during sexual intercourse, and many people who use them find that they enhance sexual intimacy. A good lubricant should be water-based and compatible with rubber products like diaphragms or condoms. Lubricants should be easy to apply within the vagina. They can typically be purchased in the pharmacy, grocery store, or online. When using lubricants, it is suggested to have a small hand towel close by for easy clean-up. Many lubricants require reapplication during intercourse, so patients should be advised to keep the bottle handy for reapplication. Petroleum-based products such as mineral oil, petroleum jelly, and edible oils should be avoided within the vaginal vault; they can interfere with helpful vaginal bacteria, can disrupt the bacterial balance, and have also been known to weaken condoms. Sexual DevicesSexual devices such as vaginal dilators or self-stimulators are helpful when vaginal shortening or narrowing has occurred. Scar tissue can impede penetration, causing dyspareunia. Vaginal dilators with lubricants can help lengthen and widen the vagina and loosen the scar tissue that may contribute to tenderness and distress associated with vaginal intercourse. Ongoing supportive physical therapy is essential, and often behavioral therapy can be influential for continued compliance. The Eros (UroMetrics; St. Paul, Minnesota) clitoral stimulator has been prescribed for patients who have had cervical cancer and for some with intravaginal radiation. Others who have used the device with success include those with other pelvic cancers, such as rectal and vaginal cancers. The Eros stimulator is the only device currently approved by US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of female sexual complaints. It is a battery-operated device with a suction cup that fits around the clitoris and facilitates engorgement. The device is expensive, but if the diagnosis is clearly documented in the patient's chart, insurance will often cover the cost. Pharmacotherapy: EstrogenSexual pharmacology remains the mainstay of treatment for many female sexual complaints. A number of healthcare providers advocate systemic hormonal therapy with estrogen, progesterone (if the woman has a uterus to prevent endometrial hyperplasia), and varying degrees of supplemental testosterone. The discussion of hormonal therapy is beyond the scope of this article and the reader is referred to the North American Menopause Society or the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists for further product selection and specific choice details. The Women's Health Initiative (WHI) results sparked much controversy and have had an impact on patient perception of hormonal therapy and physician prescribing patterns.[12,13] Many women are fearful of systemic estrogen therapy because of the increased risk for breast cancer and cardiovascular effects; many are opting for minimally absorbed local estrogenic therapies that can effectively treat vaginal complaints. In 2003, the FDA stated that local estrogen therapy should be used for the treatment of moderate-to-severe symptoms of vulvar and vaginal atrophy.[14] There have been some concerns over long-term safety with hormonal therapy in light of the WHI studies, and many patients and healthcare providers are now exercising caution before prescribing hormones. A risk-benefit analysis is often undertaken with the participation of the patient and is documented in the patient chart. Each patient must assess the personal risk of hormones vs the benefits. Local vaginal hormones come in a variety of different application methods. Creams, rings, and tablets are the most common types of minimally absorbed vaginal estrogen products that are presently available.[15] See the Table for their dosing schedules. Table. Vaginal Estrogen Therapy

Adapted from: Pinkerton J. Vaginal estrogen therapy: The question of systemic absorption. Female Patient. 2006;31:24-26. Vaginal creams. Vaginal creams contain either conjugated estrogens or estradiol and are typically applied to both the interior of the vagina and exterior of the vulvar vault with an applicator that can be refilled and reused. Patients self-administer the quantity, and some women find creams especially soothing to the pelvic region. Others may find them messy because the cream may leak and drip. Vaginal ring. The 17 beta-estradiol-releasing vaginal silicone-plastic ring is a minimally absorbed vaginal ring that is placed within the vault every 3 months. The vaginal ring is typically inserted by the healthcare professional in an office setting to ensure that the ring is placed in the upper third of the vaginal vault. The patient can reinsert the ring on a 3-month basis or if it is expelled for any reason. The 2.0-mg dose of estradiol is released over a 3-month period. Some women find this product extremely helpful because they do not have to remember to use it on a daily basis. Others, however, find it uncomfortable, and some partners have even complained of feeling the ring during sexual intercourse. Vaginal erosions or abrasions have been associated with the vaginal ring which may also be expelled during urination, defecation, or intercourse. Some women report an increase in vaginal discharge while using the ring. Vaginal tablets. Minimally absorbed vaginal tablets (17 beta-estradiol) are another option for local vaginal estrogen therapy. The tablets are contained in a prefilled plastic applicator which is disposable and biodegradable. These tablets, which patients self-administer twice a week, are well tolerated and not associated with increased incidence of endometrial hyperplasia.[16] Advantages of this system are that it is inconspicuous, convenient to use, and does not cause a mess. A study of this system by Suckling and coworkers[17] demonstrated success rates in excess of 85% of women treated. Pharmacotherapy: AndrogensOne common but still controversial treatment for female sexual dysfunction is androgen therapy. Oral esterified estrogen with methyl-testosterone has been used in the field of sexual medicine extensively since the 1970s but it has yet to win FDA approval for the treatment of desire issues.[18] The testosterone transdermal patch was recently approved for hypoactive sexual desire disorder (HSDD) in Europe, but there is no approved medication in the United States. The long-term safety and efficacy of androgen therapy has not yet been established, but there is increasing evidence that testosterone therapy has beneficial effects on libido, mood, and bone mineral density.[19-21] One long-term safety issue is a concern that the testosterone can be aromatized to estrogen, which may reactivate or promote breast cancer cell tumor growth. Alexander and colleagues[22] published an excellent review of the available medical data of testosterone and libido in surgically and naturally menopausal women. The review systematically examined evidence from randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and reported that there seems to be value in giving testosterone to estrogen-replete menopausal women with desire concerns. Kinsberg[23] discussed the INTIMATE (Investigation of Natural Testosterone in Menopausal women Also Taking Estrogen) studies, which demonstrated that transdermal testosterone is a safe and effective treatment with minimal side effects for HSDD. The new testosterone transdermal matrix patch Intrinsa (Procter & Gamble; Cincinnati, Ohio) is a promising treatment for low libido; however, further RCTs and safety data are warranted before considering use in patients with this problem. Other agents in differing clinical stages of development include: Flibanserin. This is a 5H1-agonist/2A antagonist manufactured by Boehringer Ingelheim for the treatment of HSDD. This agent is believed to be well tolerated and is associated with minimal side effects, including nausea, dizziness, fatigue and somnolence, and increased bleeding when taken along with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs or aspirin. Phase 3 clinical trials are presently under way. Alprostadil. This is a naturally occurring potent vasodilator that has an important role in the regulation of blood flow to the female reproductive tract. Local application may increase vaginal blood flow and sensation, leading to increased sexual arousal. Several trials are under way. Alpha-melanocyte-stimulating hormone (MSH) analog: PT-141: bremelanotide. This agent is administered as an intranasal spray. It is in development for the treatment of female sexual dysfunction. Tibolone. This agent, which is currently unavailable in the United States, is thought to reduce hot flashes, increase bone mineral density, and have a positive effect on vaginal dryness. It may also improve desire but not sexual function. Studies of the impact of tibolone on lipid metabolism and hemostasis are inconclusive, and long-term effects remain unknown. Nonmedical Pharmacotherapy: Over-the-Counter SupplementsIn addition to the agents mentioned above, many nonpharmacologic therapies are being marketed directly to the consumer as sexual health enhancers. Besides having worrisome and potentially detrimental side effects, very few of these supplements have been shown in randomized trials to have any clinical effect on sexual dysfunction. Some patients may experiment with foods that are traditionally thought to enhance sexuality, such as chocolate, ginseng, oysters, and black cohosh. Although these foods are unlikely to cause adverse events, their efficacy has not been established in controlled studies. Various combination over-the-counter alternatives are also popular but have not been properly studied. DHEA. Another popular alternative substance, DHEA, has limited RCT data.[24] According to one placebo-controlled trial, raising levels of DHEA via supplementation improved frequency of sexual thoughts, sexual interest, and sexual satisfaction. DHEA has been shown to increase androgens, decrease high-density lipoprotein, and decrease sex hormone binding globulin. However, high levels of DHEA have been correlated with increased risk for cardiovascular disease in women. Consultants: Multidisciplinary ManagementConsultants are a critical element in the comprehensive multidimensional management of the female sexual health patient. Some of the many healthcare providers included in the dynamic may be:

A list of clinicians and ancillary staff who are sensitive to sexual issues should be readily available for patients who take part in sexual health programs. |

Follow-up and Maintenance

Routine follow-up of patients on local estrogen vaginal therapy and hormones is warranted to ensure efficacy and correct dosing of prescribed treatment. Ongoing evaluation and management is appropriate to assess for resolution of distressing symptoms. For those on androgen therapy, careful surveillance is advocated along with repeat bloodwork done at intervals to monitor for side effects

The diagnosis and treatment of female sexual complaints is a complex, multimodal medical psychological health concern which warrants assessment and comprehensive therapeutic modalities to achieve success and resolve complaints.

No comments:

Post a Comment