Therapeutic Switching in Bipolar Disorder: An Expert Interview With Trisha Suppes, MD, PhD

Editor's Note:

Bipolar disorder is one of the most challenging diseases to treat, encompassing the need to stabilize and prevent depressive as well as manic episodes, account for a high incidence of comorbidities, and establish an alliance with patients who may be nonadherent to treatment. Multiple classes of pharmacotherapy are approved for the various phases of the disease, and within each class there are often several options. Polypharmacy is more common than monotherapy.

The need control symptoms and prevent onset of new manic or depressive episodes calls for careful adjustments in the therapeutic regimen in cases of nonresponse, partial response, or intolerable adverse effects.

Jane Lowers, Editorial Director for Medscape Psychiatry & Mental Health, interviewed Trisha Suppes, MD, Professor of Psychiatry at Stanford University and lead author of the 2005 Texas Implementation of Medication Algorithms guidelines for bipolar I disorder, to discuss principles of safe therapeutic switching.

Medscape: The Texas algorithms were published in 2005.[1] Is there anything substantial that has changed in treatment of bipolar since then that we ought to address?

Trisha Suppes, MD: The American Psychiatric Association algorithms are almost done, and we hope to see them released in early 2009. The role of antidepressants in treatment of acute bipolar depression continues to be an important issue of discussion. There's The New England Journal of Medicine study[2] that said that antidepressants weren't better than placebo. The data are not strong for using antidepressants in bipolar depression. The APA algorithms don't recommend them as a first-line option, similar to the Texas Algorithms where it also wasn't a first option. I think that the goal of treatment algorithms is to present the data in a cohesive fashion, and then people can adapt it to their use. I think it's really important to try to stick to the evidence-base: That is what really informs our treatment decisions. Clinical judgment can be applied in an individual situation, but the overall goal is to use the evidence base to guide treatment decisions.

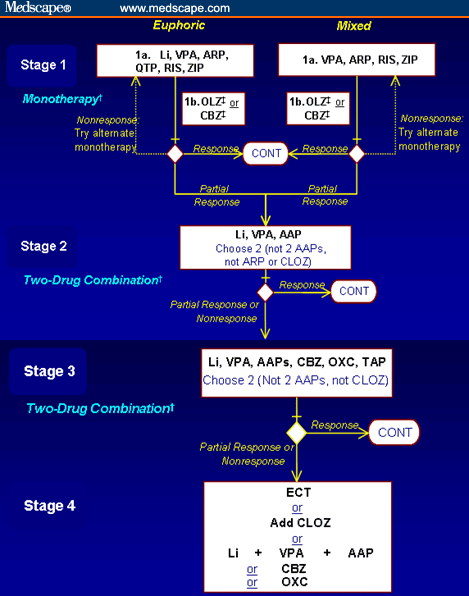

Figure 1. Algorithm for treatment of bipolar I disorder - currently hypomanic/manic.*

From Suppes T, et al. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66;7:870-886.[1] Copyright 2005, Physicians Postgraduate Press. Republished by permission.

*It is appropriate to try > 1 combination at a given level. New trials from each stage can be labeled Stage 2 (1), Stage 2 (2), etc.

†Use targeted adjunctive treatment as necessary before moving to next stage: Agitation/Aggression - clonidine, sedatives; Insomnia - hypnotics; Anxiety - benzodiazepines, gabapentin.

‡Safety and other concerns led to placement of OLZ and CBZ as alternate first-stage choices.

AAP = atypical antipsychotic; ARP = aripiprazole; BUP = bupropion; CBZ = carbamazepine; CLOZ = clozapine; CONT = continuation; ECT = electroconvulsive therapy; Li = lithium; LTG = lamotrigine; OFC = olanzapine-fluoxetine combination; OLZ = olanzapine; OXC = oxcarbazepine; QTP = quetiapine; RIS = risperidone; TAP = typical antipsychotic; VEN = venlafaxine; VPA = valproate; ZIP = ziprasidone

Medscape: The updated Texas algorithms set the goals of symptomatic remission, full return of psychosocial function, and prevention of relapse and recurrence. In the acute hypomanic, manic, or mixed episodes, the initial recommendation is monotherapy with either valproate, one of several second-generation antipsychotics, or, if the patient is euphoric, lithium. If the patient is nonresponsive to the first pass, the first recommendation is to switch to a different agent. Depending on where you started treatment, what would you need to consider when switching?

Dr. Suppes: I think we need to talk both about nonresponse and partial response. For real nonresponse the main thing is you want to be sure you've given the medication trial adequate time and at a sufficient dose, assuming you're not limited by side effects.

So for example, with lithium you would want to be over 0.8 Eq/L and theoretically you would want to give it at least a couple of weeks to see if there's a beginning of a response. That would be an adequate level for at least a minimum amount of time. With other agents, some of which work a little more quickly, again, you just want to be sure you're at an appropriate dose for long enough time to assess response fairly. This is again for the nonresponse case.

Let's say you've decided that there is no response -- not limited by side effects, but clinically nonresponsive to an adequate trial. The key factor or approach to switching is to use an overlap and taper method. Let's say they've been on the lithium. You want to continue in monotherapy, but you're going to switch to an anticonvulsant such as valproate. You would not stop the lithium; you would start the valproate and then as the valproate comes onto higher doses over say first 10 days, you would decrease the lithium so that you were taking at least 2 weeks to taper it. Now, this is assuming again, no really strong side effects and no medical reason that would necessitate a more rapid taper.

That's just a kind of overview. The main point here is that you don't abruptly stop one medication and start another. In some of the other major psychiatric illnesses that is often the approach were 1 medicine is stopped and another started. This can be a truly dangerous procedure if you do it with patients with bipolar disorder. Abruptly stopping can lead to an increase in the rebound effect of symptoms. This has now been shown with lithium and as well as with some other drugs.[3,4]

In bipolar you may be switching medications fairly frequently depending on the patient's symptoms. As long as the side effects aren't intolerable and there are no medical issues, you would want to taper over a couple of weeks. Now, if you're in an inpatient setting and the patient hasn't been on the drug very long, then you might decrease more quickly. You might taper over just a few days. The overall goal is to avoid abrupt discontinuation of the medication.

Medscape: What about partially responsive cases?

Dr. Suppes: The second case is the partially responsive case, which I actually think is the much more common situation. Patients usually exhibit some degree of response, but it is not an adequate or full response.

Often in a partial response you'll find the patient is on the medication a little bit longer. Maybe it's been 3 or 4 weeks, they are sort of doing better, but you've maxed out whatever the dose is that they can tolerate, or it is the appropriate dose, and they are just not as well as they can be. You still are working on the idea that you want to try and use monotherapy. There is a minority of patients with bipolar disorder who can do well on monotherapy, and you want to minimize the number of meds that are necessary. I think it increases the likelihood of adherence and decreases side effects, so that's always a general principle.

So in the case of the partially responsive patient, again, the overlap-and-taper procedure is even more important because they will have been on the drug for longer. They have had a partial response so you don't want to cause greater instability in the brain by abruptly discontinuing [a medication].

In that case, again, let's say they've been on the valproate now for 3 or 4 weeks, we'll go the other direction and switch to lithium. The plasma levels are up around 80-90 mg/L, which would be viewed as adequate, and you want to taper it off.

You start the lithium, and as you spend a week or 2 even bringing the lithium up to full dose, you can gradually begin to taper the valproate. In some sense, you will have the addition of lithium leading the tapering of the valproate. So you add the lithium, you wait a little bit, and then you go up on the lithium and at that point begin to taper the valproate. Again, this is all in the effort to try to use 1 drug and maximize the response.

Medscape: Are the considerations any different if you were switching between 2 drugs in the same class, say 2 of the second-generation antipsychotics?

Dr. Suppes: Yeah, I think that's a very nice question. I would have to say the principles would be the same. And the reason is the second-generation antipsychotics, while lumped together in 1 class, all have very different mechanisms of action if you look at the pharmacology. There are similarities, there's overlap, but they also really have quite different mechanisms. So again, I would encourage you do overlap and taper; obviously, you don't want to cause significant side effects. Abrupt starting and stopping medications in bipolar generally is not the appropriate way to go.

Medscape: As you mentioned, many patients don't respond well to monotherapy. As you begin combining different drugs within a class or across multiple classes, how does that then complicate the decision-making process and the control over adding or subtracting individual agents?

Dr. Suppes: The majority of patients do require combination therapy. Each of these drugs has somewhat different mechanisms, and it may be that to stabilize the brain you need to approach it from 2 or 3 different angles.

Some studies have shown that the majority of bipolar patients are on somewhere between 2 and 4 psychotropically active drugs. I think it's important to keep your expectations in check and also to communicate with your patients to keep their expectations in a kind of reasonable vein.

Let's just say you're on lithium plus a second-generation antipsychotic. If it's not clear which is the key drug, you may be shifting the drugs around to minimize the side effects or you might trade out 1 second-generation antipsychotic for a different second-generation antipsychotic and keep the lithium onboard. In that case, you still want to overlap and taper. The goal is to not destabilize the brain and the way to avoid that is to make changes gradually.

Now, in the lithium studies we did,[3] there appeared to be a significant rebound effect with abrupt discontinuation of lithium in patients with well-stabilized bipolar I disease. In fact, there was a very significant difference in that rebound effect in bipolar I and II patients when you gradually taper over 3 or 4 weeks vs a more abrupt discontinuation. So there are clinical data to support that these are important procedures, and theoretically we can also say that there are reasons to do this given that all of these drugs operate under somewhat different mechanisms as they stabilize symptoms in patients with bipolar disorder.

Medscape: It sounds like fairly consistently, regardless of what you're doing, the safe tapering is really the key message here.

Dr. Suppes: It is. I think it's the most important thing. For example, I've treated patients with really treatment-resistant bipolar disorder and we did a study where we added clozapine to existing drug regimens. These patients were on 4 or even 5 different psychotropic meds and we added clozapine on top at a very low dose, and then once it was onboard, we began to pull down the other meds. Even though they were on complicated regimens, we still applied that same principle.

Figure 2. Algorithm for the treatment of BDI - currently depressed.*

From Suppes T, et al. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66:870-886.[1] Copyright 2005, Physicians Postgraduate Press. Republished by permission.

*Note safety issue described in text.

†LTG has limited antimanic efficacy and, in combination with an antidepressant, may require the addition of an antimanic.

‡SSRIs include citalopram, escitalopram, fluoxetine, paroxetine, sertraline, and fluvoxamine.

AAP = atypical antipsychotic; BUP = bupropion; CBZ = carbamazepine; CONT = continuation; ECT = electroconvulsive therapy; Li = lithium; LTG = lamotrigine; MAOI = monoamine oxidase inhibitor; OFC = olanzapine-fluoxetine combination; OXC = oxcarbazepine; QTP = quetiapine; SSRI = selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor; VEN = venlafaxine; VPA = valproate

Medscape: Let's talk a bit about the depressive side. Standard antidepressants are at the bottom of the algorithm, once you've worked through everything else.

Dr. Suppes: Well, the evidence at this point does not support their use as a top line choice.

Medscape: Based on the 2005 Texas algorithm, whether the patient is taking an antimanic or not, lamotrigine would be one of the first things you would add if the patient is in a depressive stage.

Dr. Suppes: I think the evidence in support of lamotrigine has shifted since those algorithms were written. More studies have been completed, and the evidence to support use of lamotrigine in acute treatment of bipolar depression is not compelling.[5] So lamotrigine, at this point, has indications for the maintenance phase of bipolar disorder and the prevention of depression and mania. There is no [US Food and Drug Adminstration] FDA indication at this point for lamotrigine as a primary first-line treatment for acute depressive episodes in bipolar disorder.

Medscape: In that case, where would you initiate treatment for an acute depressive episode of bipolar?

Dr. Suppes: In terms of where the evidence base takes us, interestingly, second generation antipsychotics -- monotherapy quetiapine or olanzapine in combination with fluoxetine -- both have FDA approval for the treatment of bipolar depression and very strong studies, particularly for quetiapine.

The thing to take into account in the second-generation antipsychotics is that you have to do more monitoring. You have to be sure there are not significant side effects that will be deleterious for both the immediate or long-term health of the patient. This may include metabolic issues, such as weight gain, and also in some cases even extrapyramidal side effects.

It is also appropriate to evaluate patient history and use clinical judgment, and adapt the treatment guidelines to the individual situation with the patient. For example, if the patient is on some antimanic agent and has a history of very good acute depression response with the addition of lithium and lamotrigine, it would not be recommended that you reinvent the wheel.

Medscape: Let's talk a little bit about other aspects related to finding and keeping a good treatment response. Generally speaking, there is some evidence of dose variability in going from one generic to another, branded to generic. Does that play a role in treating bipolar disorder?

Dr. Suppes: I've seen this in patients -- and it's just very anecdotal -- where they didn't respond to the branded or they didn't respond to the generic. I just think there's an individual difference in this. I don't have a good answer for why that was the case, at all. I was surprised at the time; it didn't make sense to me, but there was a clear difference.

These drugs are a little different so I don't think that it's the case that branded is necessarily better than generic or generic is better than branded. The drugs are formulated a little differently. They are well regulated. I don't think there's any reason not to use generics, but they can be a little different in their response.

Medscape: The underlying message there is to keep a close eye on how your patient is responding.

Dr. Suppes: Yes, and be willing to try different things.

Medscape: Let's talk about one of the issues we haven't addressed yet, and that is adherence. You mentioned earlier how you can titrate up or down with doses in a controlled inpatient setting, but not all these patients are inpatient. Bipolar patients are notoriously nonadherent. How does that play into trying to maintain an effective level of therapeutic response even as you're titrating up and down?

Dr. Suppes: I do not consider myself a manager with these patients with bipolar disorder. I consider myself a consultant. My goal is to educate them. Obviously there are exceptions and that's a broad remark on my part, but my goal is to educate them so that they will manage and moderate their medications and communicate with their doctor.

If they are having trouble sleeping for a couple of nights, I want to have a plan in place so they can adjust and take medicines to help them. The data that I am aware of in adherence studies suggest that the more control you can give the patient, the more likely you are to get ongoing adherence.

I also think that with bipolar patients in particular, it doesn't work very well to try to manage them. It works much better to try to collaborate with them. If they don't think they need the medicines, no amount of my talking is going to make them take them. They'll sit there and nod and they'll go home and they'll do what they want.

I really try to spend a lot of time focusing on the education component in my work with patients so that they will see a reason for them to take the meds. I don't think it's perfect; I'm sure they take them very differently sometimes than how I prescribe them. In fact, I know they do. You have to have a high tolerance for that level of ambiguity, I think, to work with patients with bipolar disorder.

No comments:

Post a Comment